I’m not sure who it was, but some very wise observer once commented, “We are all disabled in our own ways.” Some overcome their disabilities to succeed. Others hide them. Some people have even become famous because of them.

In this regard, artists are little different than most other such people. We have all no doubt seen photos of painters so intent upon expressing themselves they have learned to paint with the brush in their mouths.

I used to warn my students in handling brushes and pencils in the classroom to be careful, since there wasn’t much demand for blind artists. Yet, I think I vaguely recall writing about one here several years ago (perhaps just nearly blind). Beyond that, I once graduated a student who went on to become an art therapist, one who helped people overcome their disabilities through art. As for my own disabilities, in getting older, my eyesight has grown weaker and my wife tells me my hearing is fading (I think she’s imagining). Fortunately, in my case, the Italians invented eyeglasses around 1286 and today, a store in the mall makes them “…in about an hour.”

Slava Raškaj is said to have been the most outstanding Croatian watercolor artist of the latter part of the 19th-century.

She was not blind, but was born deaf in 1877. Thus, not only could she not hear, she could speak intelligibly only with great difficulty. She was born Friderika Slavomira Olga Raškaj in the small, northern Croatian town of Ozalj near the Slovenian border.

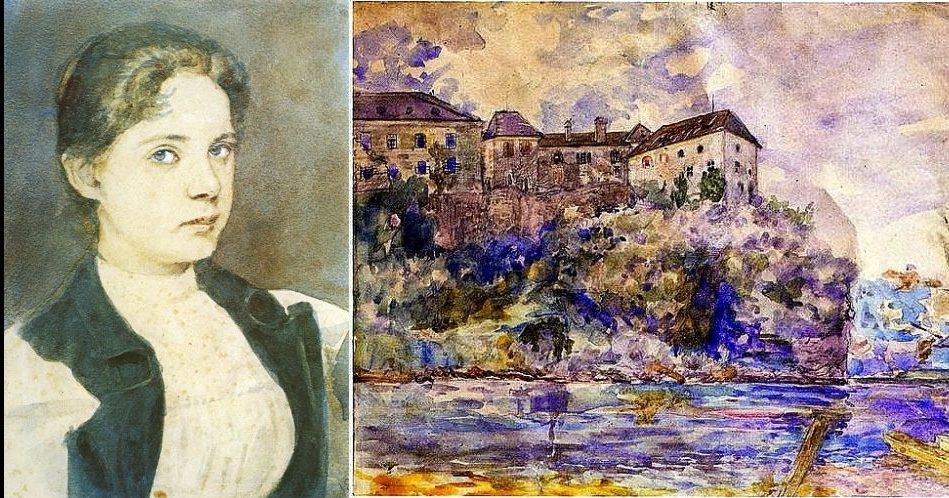

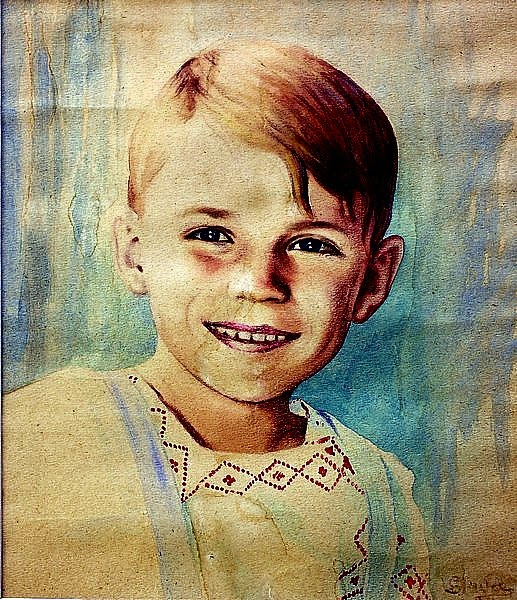

Her mother ran the local post office and was an amateur watercolorist who passed on her interest in art to her two daughters, Slava and Paula. At the age of eight, Slava was sent to Vienna to a school for the deaf where she honed her stills in drawing. A bright and quite attractive young girl (left), despite her inability to hear, she learned to speak both German and French while working to perfect her watercolor technique.

Upon finishing school and returning home, a local teacher prevailed upon her mother to send her to Zagreb for further art instruction under the renown painter, Vlaho Bukovac, only to discover he refused to be bothered with teaching a women, and one with communication difficulties at that.

Slava’s disappointment was relieved with the Croatian history painter, Bela Čikoš Sesija, took her into his own studio where he began teaching her for next two years. She lived at the State Institute for Deaf-mute Children and opened her own studio in a spare room at the local morgue.

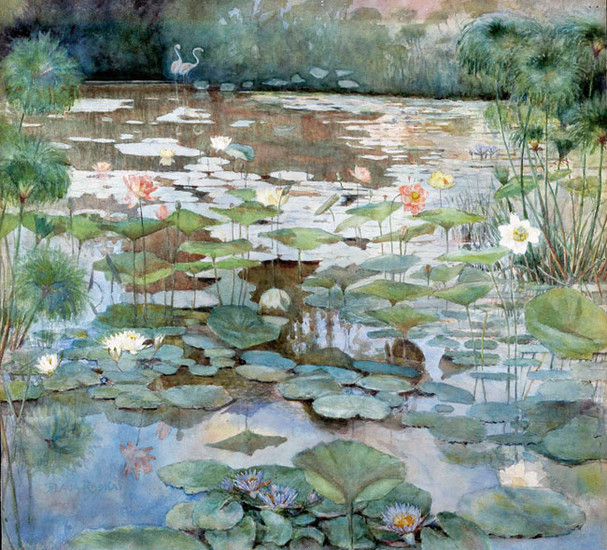

Quite apart from her handicap, or perhaps because of it, Slava Raškaj was not a typical artist. She took up painting outside, even in winter, at a time when few artists in Croatia, especially women artist, did so. She seems to have relished a rather solitary lifestyle, choosing subjects which today can be seen as reflecting her loneliness.

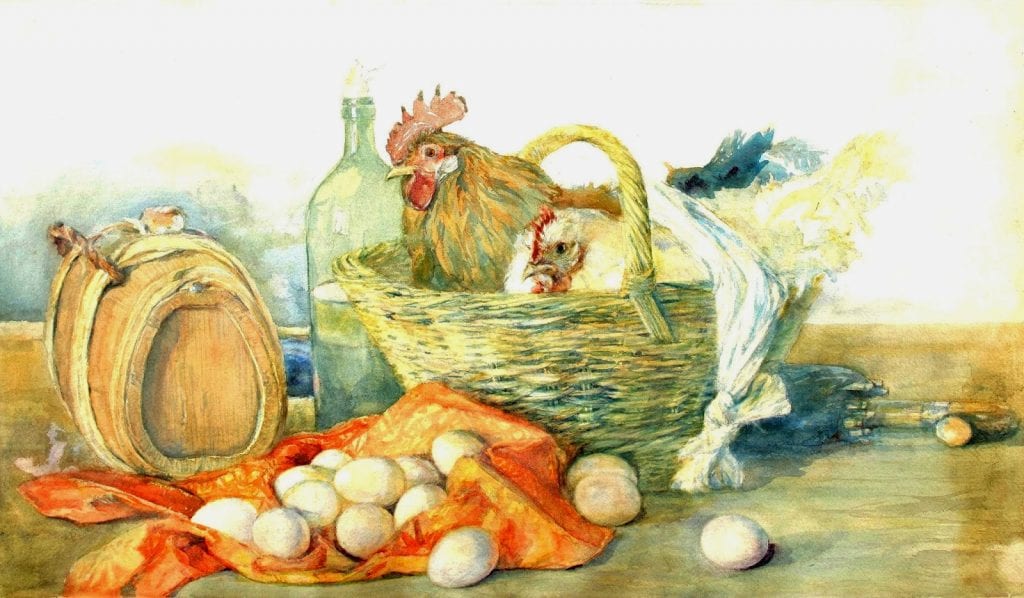

Her still-lifes often feature strange juxtapositions of items. Many artists have included eggs in their still-lifes, but few have ever dared paint both the eggs and the chicken, not to mention a rooster added for good measure. Her “A Yellow Cock and White Chicken” (above), is not just an exceptional still-life of a no-doubt difficult subject, but all the more so in being so well rendered in watercolor. Notice the two fowl are tied down.

Around 1889, Raškaj began painting inside the Zagreb Botanical Gardens. Her “Water Lilies in the Botanical Garden” from 1899, ranks as one of her best. She painted several. “Lotus for My Parents” stands apart from the others for its vertical format, not often seen in such works.

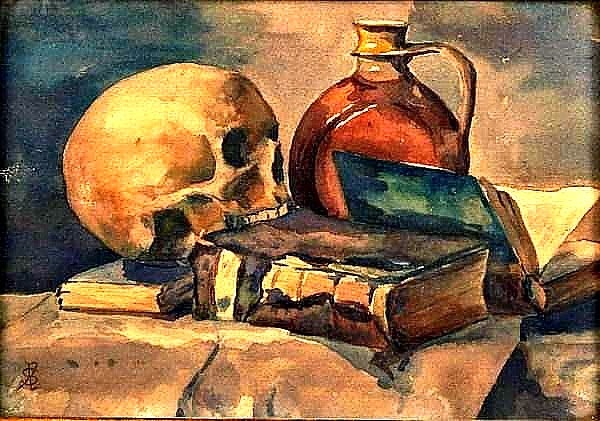

As time progressed, Raskaj’s still-lifes became rather macabre as seen in her Dead Nature.

Nonetheless, during the early 1890s, she turned out some of her best work, including the rather startling group of migrating deer. She seems not to have been any less adept at painting portrait watercolors than still-lifes or nature.

Her own self-portrait, as well as the young child (below) are both outstanding in that portraits in watercolor require skills most such artists seem not to possess (or wish to display, at least). Her title for the child’s portrait seems to suggest he may have been every bit as much trouble as the poultry.

Raškaj’s watercolors were first displayed in St. Petersburg in 1898 and a years later at the Exposition Universelle in Paris. About the same time, she began exhibiting symptoms of depression. She was hospitalized for a time then released to her family for home care.

However, her condition continued to worsen. She was institutionalized in 1903 at a psychiatric hospital where she died of tuberculosis in 1906. She painted nothing after about 1901.

Nearly a century passed before Raškaj’s work came to be appreciated.

Around 2004 a short film was made about her life and a large retrospective of some 185 of her works was presented at a Zagreb art gallery. Croatia issued a stamp featuring one of her paintings while a Zagreb bank issued a commemorative coin with her visage engraved upon it. However, perhaps the ultimate tribute to her work can be found in the fact that the Internet is rife with fakes, forgeries, and counterfeits of her watercolors.

STORYTELLING: Jim Lane